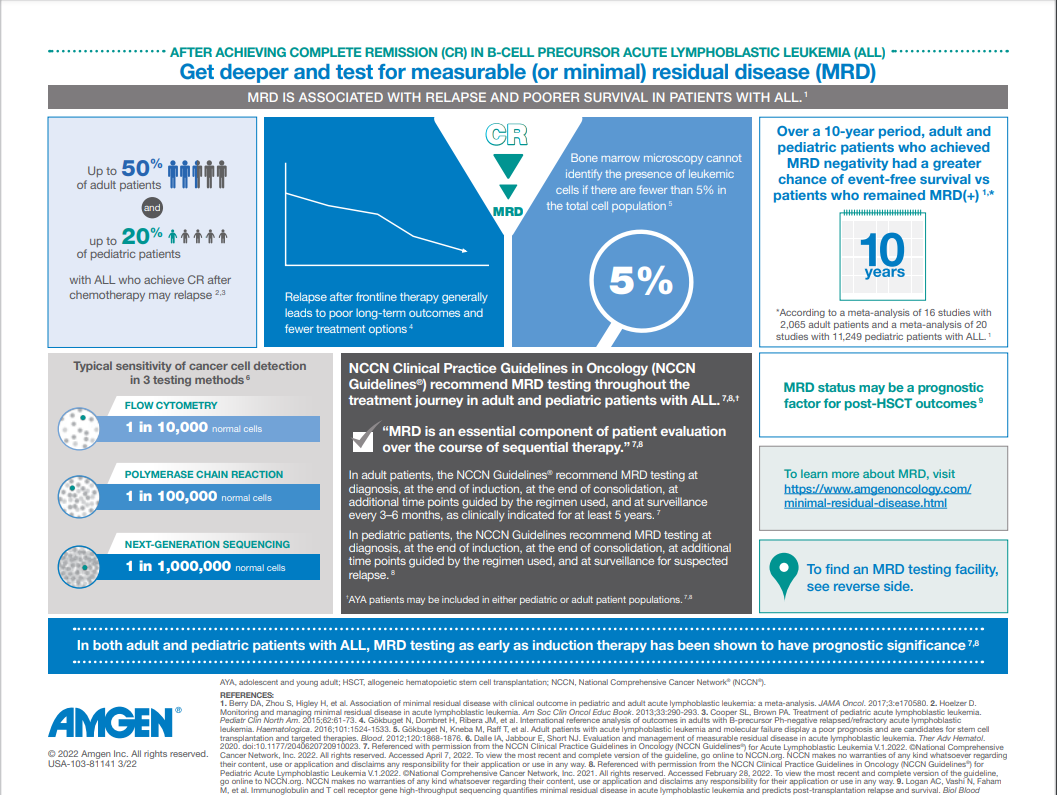

The persistence of cancerous cells after treatment, known as measurable or minimal residual disease (MRD), may lead to relapse1,2

Even after morphologic complete remission (CR), small traces of malignant cells can remain and lead to relapse, limited treatment options, and poor patient outcomes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and multiple myeloma.3,4

Evolving science and knowledge of MRD as a key prognostic indicator is shaping treatment choices and overall patient management.3

As part of our ongoing commitment to improving patient outcomes, Amgen continues to explore innovative approaches for eradicating MRD across multiple hematologic malignancies. Amgen is leading the way in MRD(+) B-cell precursor ALL and is committed to advancing the science to fulfill our mission of serving patients.

MRD IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA

MRD IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Going deeper by measuring MRD

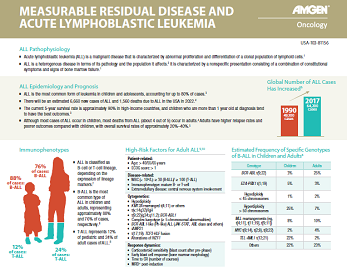

In ALL, measurable residual disease (MRD) is defined as the presence of detectable leukemic cells within the bone marrow during morphologic CR.5 The definition of MRD positivity has yet to be standardized, but a sensitivity threshold of 10-4 (or 0.01%, 1 cancer cell in 10,000 normal cells) is commonly used and may guide clinical outcomes.6

A substantial proportion of adult patients with ALL relapse despite achieving morphologic CR, with a reported relapse rate of 40%–50%.7 Furthermore, patients may still have detectable residual disease despite achieving CR with morphological testing.8

- Approximately 30%–40% of patients who achieve CR may still test positive for MRD1,9,10,*

MRD as a prognostic indicator

Measurable residual disease (MRD) is a strong prognostic indicator for survival outcomes and relapse in ALL.3,8

- In a meta-analysis (N=13,637), the presence of MRD after induction or consolidation therapy was associated with negative outcomes.3,† A significant benefit was seen in overall survival (OS) in adult and pediatric patients with ALL who achieved MRD negativity3

Impact of MRD status on OS: Adult ALL3

Impact of MRD status on OS: Pediatric ALL3

- Additionally, a retrospective study observed that MRD positivity at the time of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in first CR was significantly associated with hematologic relapse11,‡

Cumulative incidence of hematologic relapse based on MRD status11

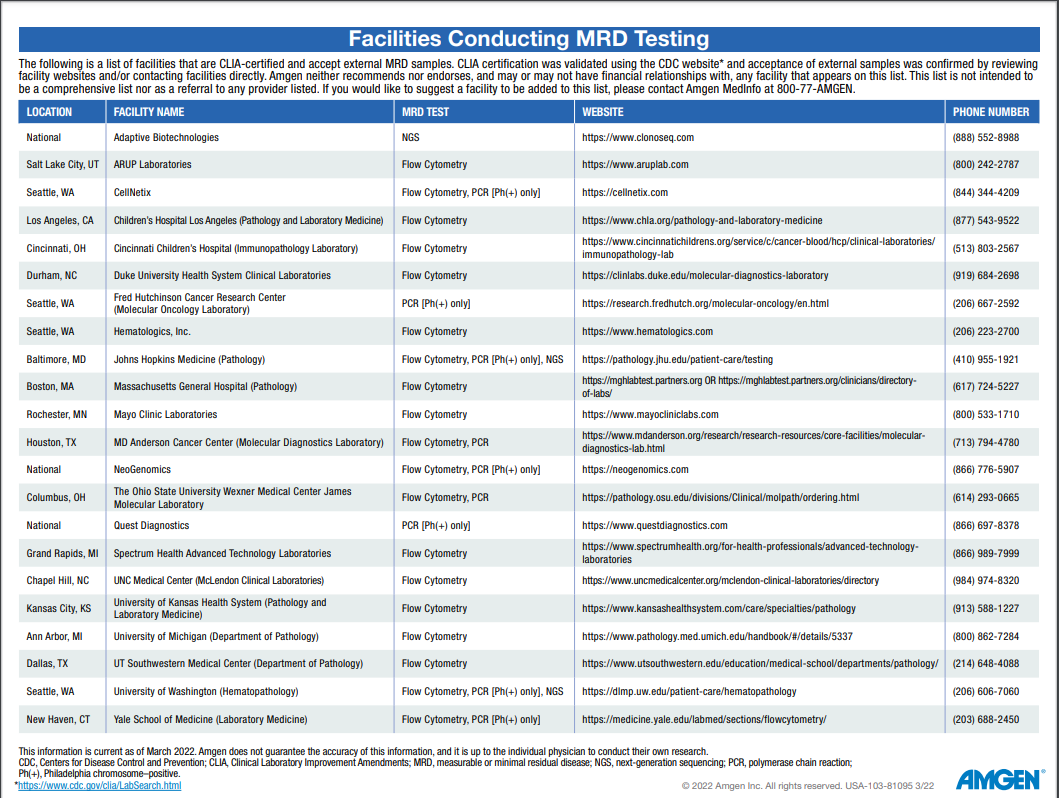

Detecting MRD

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for ALL state that a bone marrow sample from the first or early small-volume (up to 3 mL) pull is preferred for measurable residual disease (MRD) testing.12

There are 3 common techniques used to quantify MRD in ALL:13

| Flow cytometry |

|---|

| Target Aberrant leukemia-associated immunophenotypes13 |

| Typical sensitivity 1 cancer cell in 10,000 normal cells13 |

| Additional considerations Baseline sample preferred but not required13 Fresh sample necessary13 |

| Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| Target Immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor gene rearrangements or abnormal gene fusions (eg, BCR-ABL1)14 |

| Typical sensitivity 1 cancer cell in 100,000 normal cells13 |

| Additional considerations Baseline sample required13,§ |

| Next-generation sequencing |

| Target Immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor gene rearrangements13 |

| Typical sensitivity 1 cancer cell in 1,000,000 normal cells13 |

| Additional considerations Baseline sample required13 |

| Flow cytometry | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction | Next-generation sequencing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Aberrant leukemia-associated immunophenotypes13 | Immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor gene rearrangements or abnormal gene fusions (eg, BCR-ABL1)14 | Immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor gene rearrangements13 |

| Typical sensitivity | 1 cancer cell in 10,000 normal cells13 | 1 cancer cell in 100,000 normal cells13 | 1 cancer cell in 1,000,000 normal cells13 |

| Additional considerations | Baseline sample preferred but not required13 Fresh sample necessary13 |

Baseline sample required13,§ | Baseline sample required13 |

NCCN Guidelines® recommend testing for MRD

NCCN Guidelines state that measurable residual disease (MRD) is an essential component of patient evaluation over the course of sequential therapy in pediatric and adult patients with ALL.12,15,**

MRD testing timeline12,15

Get more facts about MRD testing for your practice

Watch the following videos to learn about MRD in B-Cell Precursor ALL

*Range based on three clinical studies in which MRD was measured at different time points.1,9,10

†According to a meta-analysis of 39 publications of distinct studies with 13,637 patients.3

‡According to a retrospective study evaluating the cumulative incidence of hematologic relapse in 257 patients with Ph(+) ALL who underwent HSCT in first CR.11

§A baseline sample is only needed for Ig/TCR gene rearrangements. A baseline sample is not required for abnormal gene fusions.13

**AYA patients can be included in either pediatric or adult patient populations.12,15

††Dependent on MRD testing technique used.12,15

‡‡Additional time points should be guided by the regimen used. Serial monitoring frequency may be increased in patients with molecular relapse or persistent low-level disease burden.12,15

§§Additional time points should be guided by the regimen used.15

***MRD testing may be included with a bone marrow aspirate.15

Clinical relevance of MRD

Minimal residual disease (MRD) in multiple myeloma refers to the presence of residual myeloma cells in the bone marrow after an observed response.2,4 The 2016 International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) consensus criteria recommends a minimum sensitivity of 10-5 when defining MRD negativity.4 The presence of MRD may lead to disease progression and relapse in multiple myeloma.4

MRD as a prognostic indicator

Minimal residual disease (MRD) is a prognostic indicator for survival outcomes in multiple myeloma.16

- In a meta-analysis, MRD negativity was associated with improved PFS (n=1,273) and OS (n=1,100) in patients with multiple myeloma16,†††,‡‡‡

Impact of MRD status on PFS in multiple myeloma16

Impact of MRD status on OS in multiple myeloma16

- Additionally, a recent meta-analysis of 6 studies (N=3,283) in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) observed that MRD negativity was associated with improved PFS, supporting MRD as a surrogate endpoint for PFS in clinical trials17,§§§

Detecting MRD

There are several techniques used to quantify minimal residual disease (MRD) in multiple myeloma:

| Flow cytometry |

|---|

| Target Normal versus abnormal plasma cells through detection of cell-surface marker expression18 |

| Peak sensitivity 1 cancer cell in 1,000,000 normal cells19 |

| Additional considerations No baseline sample required19 Fresh sample necessary19 Requires bone marrow aspirate18 |

| ASO-PCR |

| Target VDJ heavy chain regions for detection of immunoglobulin rearrangements18 |

| Peak sensitivity 1 cancer cell in 1,000,000 normal cells19 |

| Additional considerations Baseline sample required19 Fresh sample not necessary19 Requires bone marrow aspirate18 |

| Next-generation sequencing |

| Target Clonal immunoglobulin VDJ gene rearrangements18 |

| Peak sensitivity 1 cancer cell in 1,000,000 normal cells19 |

| Additional considerations Baseline sample required19 Fresh sample not necessary19 Bone marrow aspirate or peripheral blood sample acceptable18 |

| PET/CT |

| Target Detection of lesions demonstrating metabolic activity along with morphologic information; detection of extramedullary disease4,19 |

| Peak sensitivity Variable19 |

| Additional considerations N/A |

| Flow cytometry | ASO-PCR | Next-generation sequencing | PET/CT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Normal versus abnormal plasma cells through detection of cell-surface marker expression18 | VDJ heavy chain regions for detection of immunoglobulin rearrangements18 | Clonal immunoglobulin VDJ gene rearrangements18 | Detection of lesions demonstrating metabolic activity along with morphologic information; detection of extramedullary disease4,19 |

| Peak sensitivity | 1 cancer cell in 1,000,000 normal cells19 | 1 cancer cell in 1,000,000 normal cells19 | 1 cancer cell in 1,000,000 normal cells19 | Variable19 |

| Additional considerations | No baseline sample required19 Fresh sample necessary19 Requires bone marrow aspirate18 | Baseline sample required19 Fresh sample not necessary19 Requires bone marrow aspirate18 | Baseline sample required19 Fresh sample not necessary19 Bone marrow aspirate or peripheral blood sample acceptable18 |

N/A |

Applications of MRD in multiple myeloma

Response criteria in multiple myeloma has evolved over the years with advances in therapy.4

The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment was published in 2016, which defines categories of MRD negativity:4

- Sustained MRD negative

- Flow MRD negative

- Sequencing MRD negative

- Imaging-positive MRD negative

Continued research will help establish the role of MRD in the treatment continuum of multiple myeloma.4

Get an overview of MRD in multiple myeloma

†††According to a meta-analysis of 14 studies that provided data on the impact of MRD on PFS in 1,273 patients with multiple myeloma, and 12 studies on OS in 1,100 patients with multiple myeloma.16

‡‡‡MRD was measured using the following methods: MFC, ASO-qPCR, or NGS. However, analysis was restricted to techniques with a limit of detection of 0.01% or lower.16

§§§MRD was measured using the following methods: 8-color FCM, 7-color FCM, 4-color FCM, MFC, NGS, and NGF.17

ASO, allele-specific oligonucleotide; AYA, adolescent and young adult; BCI, Bayesian credible interval; CLIA, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments; CT, computed tomography; FCM, flow cytometry; HR, hazard ratio; Ig, immunoglobulin; MFC, multiparametric flow cytometry; N/A, not applicable; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NGF, next-generation flow; NGS, next-generation sequencing; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PET, positron emission tomography; PFS, progression-free survival; Ph(+), Philadelphia chromosome–positive; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TCR, T-cell receptor; VDJ, variable diversity joining.

1. Gökbuget N, Kneba M, Raff T, et al. Blood. 2012;120(9):1868-1876. 2. Paiva B, Corchete LA, Vidriales M-B, et al. Blood. 2016;127(15):1896-1906. 3. Berry DA, Zhou S, Higley H, et al. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(7):e170580. 4. Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, et al. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):e328-e346. 5. Bassan R, Brüggemann M, Radcliffe H-S, Hartfield E, Kreuzbauer G, Wetten S. Haematologica. 2019;104(10):2028-2039. 6. Akabane H, Logan A. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2020;18(7):413-422. 7. Hoelzer D. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013. doi:10.14694/EdBook_AM.2013.33.290. 8. Short NJ, Jabbour E, Albitar M, et al. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(2):257-265. 9. Beldjord K, Chevret S, Asnafi V, et al. Blood. 2014;123(24):3739-3749. 10. Brüggemann M, Raff T, Flohr T, et al. Blood. 2006;107(3):1116-1123. 11. Akahoshi Y, Arai Y, Nishiwaki S, et al. Int J Hematol. 2021;113(6):832-839. 12. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia v.2.2021. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2021. All rights reserved. Accessed October 18, 2021. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way. 13. Dalle IA, Jabbour E, Short NJ. Ther Adv Hematol. 2020;11:2040620720910023. 14. Correia RP, Bento LC, de Sousa FA, Barroso RS, Campregher PV, Bacal NS. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021;43(3):354-363. 15. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia v.1.2022. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2021. All rights reserved. Accessed October 18, 2021. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way. 16. Munshi NC, Avet-Loiseau H, Rawstron AC, et al. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):28-35. 17. Avet-Loiseau H, Ludwig H, Landgren O, et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(1):e30-e37. 18. Mailankody S, Korde N, Lesokhin AM, et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(5):286-295. 19. Paiva B, van Dongen JJM, Orfao A. Blood. 2015;125(20):3059-3068.